Chicago reader: Arts & Culture

An Art Gallery For The Living Room

Sspatz renders artmaking a collective act with their “Toolbox” exhibition at Compound Yellow.

by Maxwell Rabb

March 7, 2023

The “Toolbox” exhibition at Compound Yellow is the first public showing of the project.

Credit: sspatz

“Most of the time, the ideas come to us. They are falling into our net,” says Jonas Mueller-Ahlheim, co-founder of the sspatzcollective. When pandemic lockdowns closed art galleries in 2020, Mueller-Ahlheim and fellow sspatz cofounder, Thomas Georg Blank, were already hoping to reimagine art venues. Suddenly, their idea coincided with reality, as the world needed art outside of the gallery and inside of their homes.

The then-roommates, living together in Karlsruhe, Germany, launched sspatz’s “Toolbox” project, an art collection designed to be experienced in domestic spaces. Featuring contributions from 12 artists, the sspatz collective shipped 55 boxes packed with the same art and manuals to homes worldwide by 2021, offering people chosen by the artists an opportunity to participate in artmaking and challenging the isolation felt by the lockdowns. Now, nearly three years after its launch, sspatz is hosting its first public “Toolbox” exhibition at Compound Yellow, inviting Chicagoans to interact with artwork previously only available in the 55 original boxes.

“Toolbox” features work provided by an international group of artists: Franziska Windolf, Eva Gentner, Esther Steinbrecher, John Dombroski and Trevor Amery, Julia Dorflinger, Simon Fischer, Anas, Lukas Picard, Simon Pfeffel, Markus Vater, and Aida El-Oweidy. The components include a wooden block meant for meditation and a swimming tube meant to be inflated and deflated. Vater’s manual instructs guests to create a text piece on the walls with a brush and black watercolor. The exhibition encourages guests to manipulate and create, accompanied by instructions from the artists that can be followed or not.

The work is designed to puzzle people and inspire playfulness, challenging the traditional boundaries of art galleries, and this is especially present in Steinbrecher’s The Hand Maid’s Tale, positioned at the center of the gallery. The piece features simple household items including soap and multicolored sponges that Steinbrecher decontextualizes, saying “It’s not about solving the riddle, it’s about liberating the material.” Defining the items becomes the responsibility of others. Without active participation from others, the pieces are incomplete, giving visitors a chance to interact with art by breaking down the exclusive walls that define much of the art world. For sspatz, sharing art and exchanging ideas is essential to creation.

Three years before the lockdown, Blank and Mueller-Ahlheim formed the sspatz collective with former member Dóme Scharfenberg, because they felt disenchanted by gallery spaces and an endemic lack of exchange in art. “Toolbox” reinvents the stagnant experience of art appreciation, typically defined by silent gallery walks and impersonal observation. Instead, sspatz invites the public to participate in the artmaking process directly. “Toolbox” emerges from this desire to disrupt the exclusivity of art.

“The people that produce art are often not financially able to afford living with art from other people,” Blank says. “It’s this weird thing where we produce it and then other people live with art in luxurious places. There’s this idea that art is a part of this exclusive world. The three of us who founded sspatz had this urge that it didn’t have to be like that. You don’t need to live in a fancy mansion to live with art. You can also live with art in your shared flat in a crappy old building.”

The Compound Yellow exhibition highlights the materiality of art. For two years, recipients of the original “Toolbox” packages could manipulate the artwork by any means. The “Toolbox” becomes highly personal, obscuring the distinctions of authorship and confronting the traditional practice of artmaking. To activate the art, guests cannot simply browse an exhibition. They are required to play with the tools. Gallery visitors get the chance to take art into their own hands at Compound Yellow.

“Sspatz is something that can help us challenge things that we encounter in our professional life, because the art world, the social system, is such a heavily regulated thing with so many rules, may they be implicit or explicit. Sspatz is a platform where we can question a lot of things in terms of where art has to be presented or how art can be perceived,” Blank says.

Touching artwork is disorienting and sometimes unsettling, even when the instructions explicitly ask for it. Countless visits defined by “Do Not Touch” signs condition us to avoid overstepping in a gallery space, but Fischer’s ceramic plate is meant to be thrown, directing visitors to destroy an art piece despite their natural reluctance.

Both Mueller-Ahlheim and Blank believe that these interactions allow people to understand the art with deeper meaning. Experimentation and play becomes integral to the work, not exclusive to the artist. Similarly, Compound Yellow works to facilitate a space where creative work bleeds into everyday life and art is purposely shared. Sspatz reached out to Compound Yellow last year and cofounder Laura Shaeffer was impressed by the similarities of sspatz’s mission to her own.

“It was clear that Compound Yellow shares some fundamental interests and values with the sspatz collective,” Shaeffer says. “Showing art in unconventional spaces and domestic spaces, making contemporary art tangible as part of living spaces and testing how it can be presented and received in completely regular homes, outside of exclusive properties or pure white cube settings. Sspatz and Compound Yellow both try to blur the lines between art and everyday life and to normalize living with art.”

Mueller-Ahlheim is now finishing his master’s degree in painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Blank lives in Los Angeles, where his personal practice takes a documentary approach to the city’s manufactured landscape. “Toolbox” will be on view through March 25, though the project is conceived as an open-ended process for visitors. Once enraptured by the artwork, visitors are incorporated into an ongoing artmaking project, where the playfulness and exchange of ideas persist.

“There are so many different ways in this box that you can deal with art,” Mueller-Ahlheim says. “What I love about the ‘Toolbox’ is that every art piece requires some sort of engagement. You have to execute the artwork yourself, which gets you in touch with the process of art-making because you are a part of it. You are very much considered. It is just a beautiful thing.”

A big thank you to Maxwell Rabb and the Chicago Reader for this publication. To read Rabb’s article directly, visit the chicagoreader.com

Interview with James Jankowiak

See his exhibition “The Great Escape” new works by James Jankowiak at Compound Yellow until November 20th.

Interview by Jamie Nance

Image by Tom VanEynde

What about Chicago and its landscape helped influence your work? Is there an element of this city in your work?

The experience of living in Chicago put me on the track to make the work that I'm making. Maybe it's fair for every artist to say the same thing about where they grew up. I've lived here my entire life. When I was a young guy, I leaned on it as a way to kind of escape a lot of the problems that a lot of kids deal with here in Chicago. Then I grew up to be a mentor to a lot of young people who were also dealing with the same crap that I dealt with when I was growing up.

I also have a deep love for the history of Chicago art. My Aunt Darlene used to own a bar called the Gallery Cabaret. Ed Paschke used to go here. And, you know, when I was a teenager, I didn't realize how famous and how amazing he was. But when I found out I thought, “wow, that's so cool! He's coming to my aunt’s bar.” As a teenager when I saw an Ed Paschke painting for the first time, I was just completely blown away. Then I went down the rabbit hole and started learning about everybody else and as I got older, I realized that these Chicago artists have an international influence.

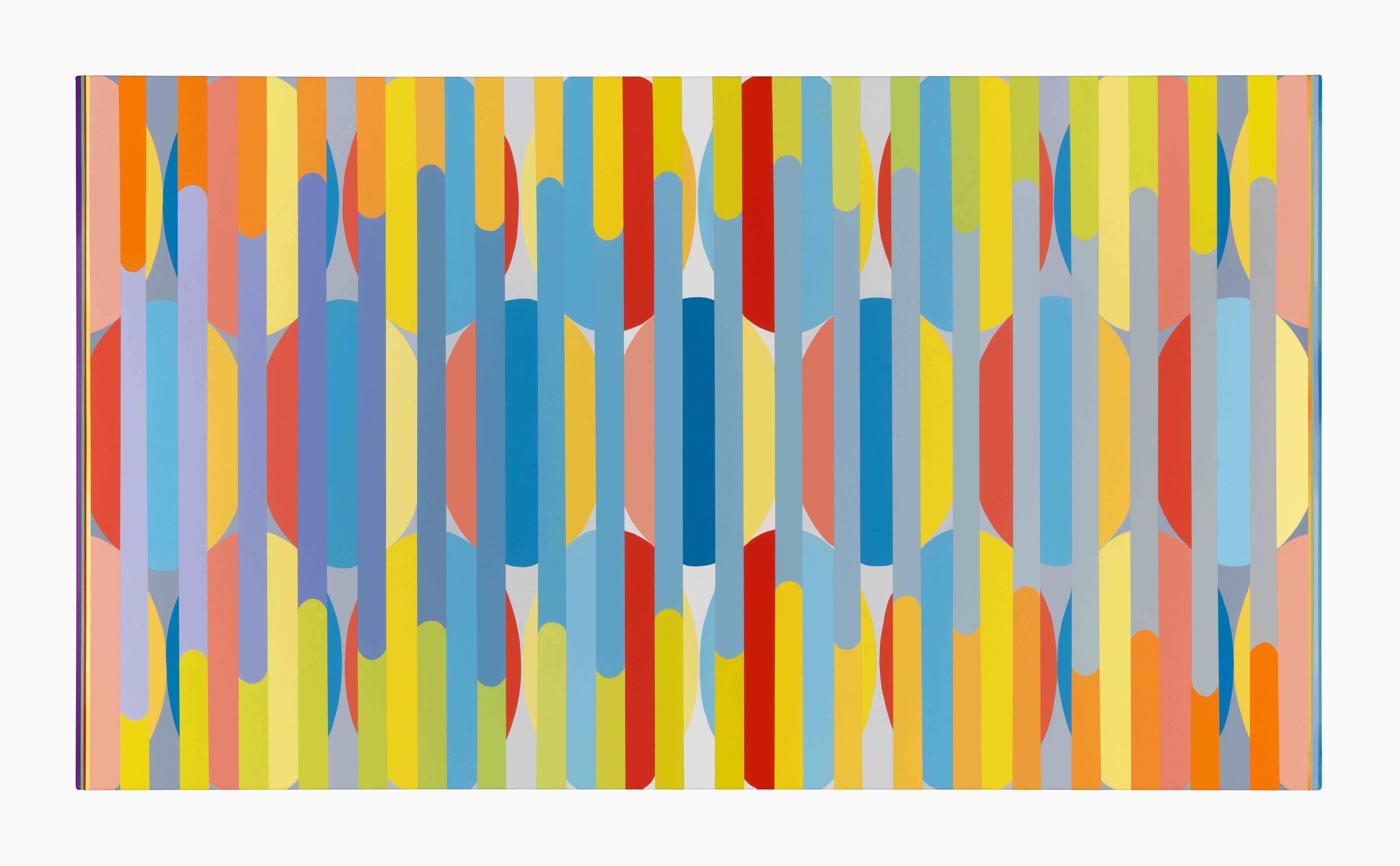

Thinking about the composition of your work, your use of color is very striking. The colors really vibrate off one another. Do you plan the colors and shapes for a painting in advance or do you work intuitively?

Actually, all the colors are planned in advance. Everything is plotted out. I'm really interested in art being a recorder of time. My work contains a lot of units which you can see in stripes or shapes, for example. There is also a lot of order in my work. I have had a lot of disorder in my life. Some artists make chaotic work and that works for them. But I have a need to order things. I use my colors as units to frame the work and create order.

Is there a significance in the shapes in your work?

I've always made associations with shapes my entire life. I can remember the moment when I never looked at shapes the same way again. When suddenly, shapes became these mystical things to me. It was in third grade. I went to Catholic school, and they made us go to church like at least twice a week. We would be sitting right in front of where the priest would be. If you misbehave, they're going to see you. Above us was a beautiful painted ceiling, very European style. I believe the church was built in 1904, back when people spent a lot of money on art. There was a painting of a triangle with an eye in it, kind of like what you see on the dollar bill. I would just sit there, looking at it, you know? And then one day, the priest saw I was not paying attention to him or something and he said, “Jimmy, do you know what you're looking at?” He said, because in Catholicism God is the father, the son, and the Holy Spirit, it's a Trinity in the triangle. There's three sides and the eye is the eye of God constantly watching you all the time. And then my little mind just got completely blown away by this association. That was probably one of the most special moments of my life, actually. I just started looking at things differently and seeing things differently. So, thanks, Father Lewis.

When you depict objects in your work, do you usually find them after the piece is in the works, or do you start with the object and it inspires the whole piece?

More so the latter. Finding it first inspires the work mostly. When you see a circle in my work, it's most likely a found circle. Like I'm not using a compass, I save all the lids of things so I could have different sizes.

How do you title your paintings?

Most of my titles are actually songs that might’ve been on repeat as I worked on the painting at the time. Some of the songs have meaning to me that makes sense to the painting. The parameters of making a work that feels like a period of time is connected to sound. Music uses timing and I translate this connection between music and timing in the titles of my work. There’s a big painting in the show called got you, which is the title of a song from a band called Amyl and the Sniffers. They’re a post punk band from Australia. I almost titled it I don't care about the things I have because I got you because that's a lyric in the song. I decided on this for the title because saying “got you” can have all these kinds of different associations and connotations. “Got you” could be like “gotcha” or “I got your attention” or “I got over it.” I like the vagueness of it. But when I look at the painting, I just remember how much I love that song and how grateful I am to be in the studio and have that moment to be able to not worry about anything except getting this painting done. I have the luxury of listening to such great music while I'm making my work. Life could suck, you know, and that doesn't suck. And I'm just grateful for a moment of not sucking. I guess it's capturing time, in this way.

You say there’s a lot of order and planning in your work. How do you really know when your work is finished? Are there parts of your work that are unplanned?

You know, I would say at this stage of my life, that doesn't come up like it used to. There's a painting in the show called Mystic Bounce which is also named after a song, a remix of a song called “Mystic Brew,” which is an old jazzy song that a Tribe Called Quest samples for electric relaxation. There's a ball bouncing in that painting. It didn't have that ball originally. I had the painting on the wall for three months and I decided at the last minute to add that. It was spurred by a studio visit with a husband and wife team. The husband comes in and he looks at the painting that didn't have the ball and he's very over the top, “beautiful!” And the wife looks at me and she goes, “is it finished?” The husband said, “how dare you, you never ask an artist that” you know, but I ask the wife, I'm like, “does it feel like it's not finished?” And she was like, “I mean, I guess I could see it finished like this.” And I'm like, “no, you felt like it wasn’t finished for a reason.” A month later I came back to it and I had her voice in my ear, and that’s how the ball was added.

Let me put it to you this way: I don't rush to resolve it. I'll wait. There's a painting in the show that I started in 2018. It's called Picture Support. You know that shape that's on there? It looks like a coffin. I actually ripped off the back of an 8 by 10 picture stand and I just tore it up and I traced it. I like using familiar images. I'll use a shape that people have seen a gazillion times in their lives and then when they see it in front of their faces, they don't know what the hell it is.

Picture Support was a response to Trumpism and to the impending fascism that was happening. It was before COVID. I put it away and I didn't look at it for three years and then I dragged it back out. I had a few friends look at it and they said, “don't do anything else to it.” but I always had this nagging feeling that I didn’t think it's done. I decided in May that I really wanted to show this painting. I knew what would finish it and I had a friend make that frame for me. I was even thinking about painting the frame a different color, but then when I saw how beautiful it looked natural. I liked the juxtaposition between the artificiality of the acrylic paint and the organic.

When you depict objects in your work, do you usually find them after the piece is in the works, or do you start with the object and it inspires the whole piece?

More so the latter. Finding it first inspires the work mostly. When you see a circle in my work, it's most likely a found circle. Like I'm not using a compass, I save all the lids of things so I could have different sizes.

Regarding your teaching artist life, I'm interested in how art gets made in a community setting?

As a teaching artist I have the liberty to bring my own practice into the classroom, whereas other teachers don't have that same freedom. They must teach to the state of Illinois standards. kids decide whether they're good at making art around grade 5. They have their preconceived notions of what art is. They’re expecting me to teach them how to draw. I just don't follow that at all because a lot of young people are completely intimidated by the idea of having to draw. I deliberately present artwork to them that looks easy. That looks accessible. I drive the point that simple shapes we see in our lives have associations and we can make any shape special. You could have a crazy life, but it might feel good to just draw a bunch of rectangles and make them feel like they're in order. It can make you feel like you're in order.

It's been successful, I think. But this year, I'm stepping back from my normal, chaotic teaching artist schedule and I'm focusing on teenagers at Hancock High School who actually helped me with some of the paintings in the show.

I was fortunate enough to get this really cool mural job this year and I proposed that I would hire as many students as I possibly could. When they weren't busy on the wall, I had them in the studio. Most of the kids that were working with me just graduated from high school and they're going to art school. They took it seriously. I had them in this space with remarkable neighbors. A couple doors away from me is an artist named Sonja Henderson, who is famous for creating the Martin Luther King Monument in Marquette Park. Well, she would leave her door open, and my students would have to walk past her studio to get to mine. She always would invite them in, share her work, and give these amazing lessons that would leave an impact on the students. One day after they spent some time with Sonja, they came to my studio afterwards and they were completely silent. And I'm like, “do you guys want me to put music on?” And one girl goes, “no…I need a minute to process what just happened.” The students get to learn so many important things. That's the beautiful thing. This ripple effect happens. One of my students got to meet another amazing painter, Jeffly Gabriela Molina, and told me that was the most special day of her life. She said, “I know what kind of artist I am now.” This girl is a junior in high school! I had grown-ups in my life trying to get guys like me to stop tagging all over the place, and they got together and gave us some canvas and some paint and let us get together every Saturday. When I was 16 years old getting free canvas, free paint, and grownups not judging you made me think, “I want to be like you one day.”

I have one final question. If you could create the most ambitious piece that you ever wanted to make and could have any artists work on it with you, who would you collaborate with?

An artist right now who's making work that I absolutely love is Julie Mehretu. She does really large-scale abstract paintings. Her abstract work is a translation of something that's representational. I really love the way her brain works, and I love the way she creates these expansive painterly spaces. Also, Bridget Riley is somebody who I absolutely love. It's obvious why I would love to work with her if you look at her work and mine.

A big thank you to James Jankowiak for sitting down for an interview. His exhibition is on display at Compound Yellow from September 18th to November 20th.